Sherlock Holmes: A London Detective

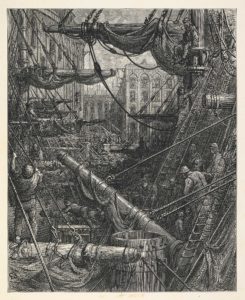

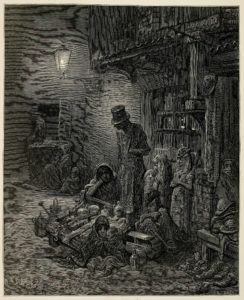

Sherlock Holmes is of course a very beloved character, and the setting of his stories being London seems to be a significant part of his character. Considering all that I’ve read so far about London in the novels and other texts (it is crowded, it is easy to blend in, it has a lot of poverty, crime is a rampant issue, etc.) I could see why Conan Doyle would be so inclined to write stories about a detective in London. During the Victorian Era, policing was a developing profession. As we read about in Oliver Twist, mobs of onlookers and other people on the street took it upon themselves to apprehend criminals. This was not (as we read) a very effective means of policing. In the first Sherlock story we read, “The Red Headed League,” we also are exposed to some of the problems/corruption with this developing force. One of the characters in on the stakeout is a police officer. He at one point says of Sherlock, “He has his own little methods, which are, if he won’t mind my saying so, just a little too theoretical and fantastic, but he has the makings of a detective in him. It is not too much to say that once or twice, as in that business of the Sholto murder and the Agra treasure, he has been more nearly correct than the official force.” His dismissal of Sherlock as someone with simply the “makings of a detective,” only “nearly more correct than the official force” (which we know is a gross underestimation of his skills and success) reveals him to be a very proud and self-serving man.

Conan Doyle’s method of writing is very easily accessible for any reader (especially in comparison with Dickens and Austen). His language is simplified, and his sentences are mostly concise. Part of what makes his stories so easily understood is how well he describes the characters, settings, props, and action of his stories; his stories are very descriptive, without overdoing it. For example, consider the following passage from “The Red Headed League”: “I had called upon my friend, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, one day in the autumn of last year and found him in deep conversation with a very stout, florid-faced, elderly gentleman with fiery red hair. With an apology for my intrusion, I was about to withdraw when Holmes pulled me abruptly into the room and closed the door behind me.” This opening to the story immediately pulls the reader into the room with Watson, creating a clear image of the scene, and especially of the man in it. That said, London, being such a big and bustling city, is a place that is full of noteworthy and descriptive people and places. Readers would easily be able to call such images to mind not only from Conan Doyle’s writing, but also from their own experiences.