Dismal London: The Portrayal of Charles Dickens and William Blake

When considering the texts we read for this course and how each portrays London, the two that stand out the most to me are “London” by William Blake and “Night Walks” by Charles Dickens. Each work highlights a lot of the negative aspects of Victorian Life in London that invoke a lot of pathos in the reader, but each author completes this task in their own unique ways.

The poem “London” by William Blake is organized in 4, 4 line stanzas which constrains the topics and style, leaving Blake a relatively short space to work with. This being said, he gets right into life in London as uses his depictions of life to set the scene, a first-person point-of-view, and his diction to create a dismal tone. In stanza one, he uses diction such “weakness”, “woe”, and “charter’d”: “And mark in every face I meet / Marks of weakness, marks of woe” (3-4). His word choice is quite interesting as he depicts the people as incapable of helping themselves. Dissimilarly with his use of “charter’d”, the city itself is presented as confined, mapped, and under government control (according to Google’s definition). This theme blaming the royalty/ government carries on within each stanza. In the second stanza, he uses words such as cry, fear, ban, and mind-forg’d manacles. Cry is repeated 3 times in the poem, and two of them are in this section; once time is found in “every man” and once referring to every infant. This stanza focuses a lot on the pain and suffering of the people in the streets. “In every voice: in every ban, / The mind-forg’d manacles I hear” (7-8). The use of “ban” again shows government or royal restriction, manacles refers to shackles or constraints (according to the google definition), and mind-forged implies that these men and children are constrained by the minds and beliefs of how others see them, as well as how they see themselves.

In stanzas 3 and 4 he moves away from broad generalizations of “every man” and “every face” to very specific encounters. In stanza 3, Blake refers to crying chimney-sweepers and blackened churches. Puling a little knowledge from Blake’s “Songs of Innocence” and “Songs of Experience” the chimney sweepers are often kids sent to work quite young, so again a child is crying. The blackened churches I read as possibly being covered in soot from the chimney, or blackening in sin and impurity as white is regularly associated with purity as well as in church ceremonies. Stanza 3 also refers to “And the hapless Soldiers sigh / Runs in blood down Palace walls” (11-12). These lines lead me to believe that Blake is blaming royalty and the government for the bloodshed and the deaths of its people as it stood back and watched. In stanza 4, “How the youthful Harlots curse / Blasts the new-born infants tear” brings a lot of emotion to some ordinarily overlooked individuals. Words such as tear, plagues, and hearse are all centered around a “new-born infant”. A harlot, being a prostitute, appears to be cursing at a newborn in the streets because the baby has plagued rapid and wide spread death on the importance and meaning of marriage. Marriage is often associated with government, conformity, and a way of life. It is symbolic that the birth of the infant is bringing an end to the prospects of marriage for the woman, as well as causing a widespread plague on marriage throughout the city. According to Blake, life is awful, dreadful, full of misery, and at the center of all of the sadness: royalty is to blame.

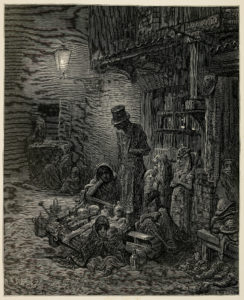

In Charles Dickens’ “Night Walks”. he has a lot more room to expand on his dismal outlook on London. He does so in a one-person point-of-view like Blake, but in the story-like fashion of a man walking through the city streets. He gives specific details of the roads he turns down, his surroundings, and of the locals he encounters with. He eases his way into the darker elements of London at night, starting off with a restless city at “half-past twelve”. It was filled with “houseless people” and he describes the drunkards, the taxis and “that specimen was dressed in soiled mourning”. He says different kinds of people and happenings late at night appear to band together with others of a similar state of mind. Throughout his story, Dickens writes from the persona of a homeless person, while contradictorily referring to the others like him as “specimen”, “it”, “savage”, “creature”, and “wild bears”. While Blake focused on who was to blame for the situations in London, Dickens seems to focus on the widespread homelessness and disease. He talks a lot of the high rate of suicides, dry-rot developing in men, and how there are more dead than there are living. He describes dry-rot in such a way that is seems as if the working class that have it all, are working themselves to both physical and mental exhaustion. The results of this overworked nature of life causes depression and loss of will to live so that they quite literally rot away and die.

“Night Walks” also has sections where children and the government palaces are referred to, though the government is referred to more sarcastically and less direct in nature than Blake. Dickens walks past the Courts of Law and he writes that they were “hinting in low whispers what numbers of people they were keeping awake, and how intensely wretched and horrible they were rendering the small hours to unfortunate suitors”. Yet, just before he calls Parliament a stupendous institution in the eyes of other nations. This quote is symbolic in that in the eyes of its own people, the government appears to be failing. Yet, while this is such an important and central cause of dismal life, this section takes up only a small paragraph in Dickens’ work. In a contrasting manor, Blake’s whole poem alludes to the situation of everyday life being the fault of parliament and royalty. The children are also not used in Dickens’ story to draw more sympathy, but describes them as hunted and uncared for savages who fight and allude police in Covent Garden: “But one of the worst sights I know in London, is to be found in the children who prowl about this place; who sleep in the baskets, fight for the offal, dart at any object they think they can lay their thieving hands on, dive under the carts and barrows, dodge the constables, and are perpetually making a blunt pattering on the pavement in the Piazza with the rain of their naked feet”.

Dickens describes how hard these men work and how tough life is, but in a different way than Blake. Blake’s poem is representing these men as consumed with sorrow and feeling sorry for themselves rather than the tough and nasty conditions of working. Blake’s poem is more effective in drawing immediate pathos through large generalizations, but Dickens’ story captures the reality of life that can only be seen at night by presenting real places, real people, and very specific scenarios. Each author carries a different tone in their approach to the topic; Blake’s is dismal and sorrow, where Dickens is shameful and disgust. Both authors are attempting to draw awareness and pathos to their depiction of life through the connection and trust offered through a first person point-of-view, but in vastly different ways of telling their story and drawing the attention of the public to their cause.